// From Chapter Four

“I can’t believe you’re planning to take that man as a patient,” Madeline Farquhar said to her husband. “You always make the wrong decisions.”

She raised her pencil-thin eyebrows and stared at him, her thin lips pursed in a frown. It was an expression George was used to, but he still felt intimidated by it. By her.

Madeline was a tall, slim woman. With her narrow face and heavy makeup, she had a severe look about her, a look that George felt she had developed, perhaps even cultivated, over the years of their marriage. She was a novelist, an Avant-garde artist, committed to breaking barriers, to creating new icons for the intelligentsia. In the early years of their marriage, she had admired George’s status as a physician, his intellectual sophistication represented by his identification with Freudian theory, which had not yet completed its descent from its position of prestige in Western culture. His degrees and his position should have made him feel as if he were her superior, although they never had. In time, she had lost her respect for him and his profession, grown to disparage what she called his “slavish” adherence to psychoanalysis, which she referred to as a “worn-out theory of human behavior.” She told him that his continued belief in the methods of psychoanalysis was a symptom of his timidity, his reluctance to try anything new, traits that she claimed characterized his personality.

“But I’m fascinated by the man,” George answered, feeling, as usual, as if he were on the defensive. “He seems to have completely denied any emotional attachment to his wife.”

“And that’s unusual?” Madeline replied. “Physician, examine thyself.” Her dark eyes, under her arched eyebrows, were filled with scorn.

“I mean he’s displaced all of the emotions he should be feeling toward his wife so they’re now focused upon his secretary,” George continued, doggedly. “That’s unusual, especially since his wife may still be alive.” Although his professional ethics forbade it, George often discussed his cases with his wife. Her curiosity, and even more, her insistence, trumped his ethical reservations. The only rule upon which he insisted was that she not use any of his revelations as material for her novels.

“But he’s in the news, George,” she said. “And so will you be as his psychiatrist.” They were in their living room, sitting in matching curved- back Queen Anne chairs, sharing their ritualistic evening gin and tonics, looking out at the sunset over the Pacific Ocean from their house’s perch high on the western side of Newport Beach’s Spyglass Hill. The sea, in the distance, was a glistening silver in the light of the descending sun. “The press has already convicted the man of his wife’s disappearance, and no doubt of her murder. The police haven’t said so directly, but the newspapers say the police are treating him as a suspect. And you, you’re considering taking this psychopath on as a client. What do you think people will say about you when he’s found guilty and it comes out that you began seeing him as a patient after he’d murdered his wife? Whatever possessed you to do such a thing?”

“You’re jumping to conclusions,” he said, feeling the sweat beginning to form under his arms. He couldn’t tell her that he hadn’t even been aware of giving Bonaventure an appointment. His history of dissociative states and their recent reappearance were something he shared with no one, least of all his wife. “The man hasn’t been accused of anything, except by the press and by people like you who can’t wait for the police to do their job. Besides, why would me seeing him for therapy get anyone’s attention? Why would the papers even mention it?” George knew why Madeline was upset. She was afraid that he would do something foolish to jeopardize their income. It was her chronic fear. His wife had grown up in an impoverished household, her father an alcoholic who was often unemployed. She acted as if the financial success she and her husband enjoyed could be wiped out at a moment’s notice. George suspected that it was his earning power as a physician that had attracted her to him, even more than the prestige of his profession, certainly more than his personality, which she rarely hesitated to disparage.

“Are you serious? Why do you think a man suspected of killing his wife would seek psychiatric help and then display symptoms that made his doctor—you—think that he’s some kind of psychotic who doesn’t know what he is doing; or more pertinently, what he might have done?”

“You think he’s trying to set up an insanity plea?”

“Don’t you?”

It had occurred to him, although he had dismissed the idea. “I don’t think that’s what’s going on. His manner was genuine. I had to drag some things out of him. The indifference he displayed regarding his wife was real, I’m convinced of that. And it’s that symptom that points to some kind of neurosis, an unhealthy, even abnormal, reliance upon repression. That would hardly serve as a basis for an insanity plea.”

“Sometimes, dear, you intellectualize things so much that you can’t see what’s right before your eyes. The man is a psychopath. He is a dissimulator. He presents exactly the kind of picture that convinces you that he has some kind of mental illness, and you fall for it hook, line and sinker.” Her expression was one of disgust.

George struggled to keep his feelings under control. It didn’t pay to show his anger around Madeline. She just got angry back and he couldn’t face that, the days of not speaking to him. He always felt abandoned. “Well I don’t think so,” he answered.

“You’re playing with fire, George.”

He was caught off guard by her use of the same phrase that Lucas Bonaventure had used in talking about both his wife and his secretary. “Are you warning me?” He looked up at her, trying to read her expression.

She scowled at him. “Damn right I am. You can’t afford to have your reputation compromised. Analytic patients don’t grow on trees, and you haven’t kept up with new developments in biological psychiatry enough to be able to do anything else. Other doctors can always fall back on something like moonlighting as emergency room physicians if their practices begin to fail. But what could you do in an emergency room, dear? I wouldn’t allow you to give me a shot and I certainly wouldn’t want you to be wielding a scalpel in my presence. You’ve become a one-trick pony, and that trick has a very limited audience.”

He had a momentary vision of standing in front of his wife with a scalpel in his hand. He felt his palms beginning to sweat. He refocused his mind on their conversation. “You never complain about the money my one trick brings in.”

“You earn well, I admit that dear. But your income is fragile. It’s built upon a fading cultural phenomenon. Look at your colleagues. They’re mostly in their seventies, some even older. You’re always dreaming of publishing your cases in one of your hallowed journals, but half of those journals have gone out of publication. Nobody’s coming into the profession but a few impressionable social workers. How many of them are going to want to claim that they received their training from the man who treated a psychopathic murderer and didn’t even know it?”

To buy The Oedipus Murders, please visit https://www.amazon.com/Oedipus-Murders-Casey-Dorman/dp/1684333318

.

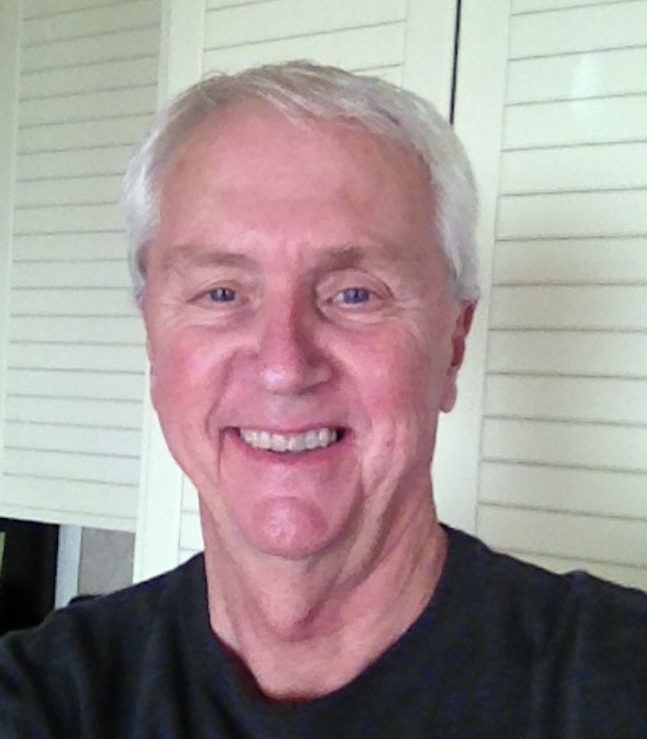

Casey Dorman enjoyed a long career as a clinical and research psychologist. He published approximately two dozen scientific articles on the brain and behavior and a book in the John Hopkins Series in Neuroscience and Psychiatry. He was the editor and publisher of Lost Coast Review, a print and online literary review, and he is the author of several novels, including the upcoming Ezekiel’s Brain (NewLink Publishing, forthcoming). He has won a number of awards for his community work in the field of mental illness. He lives with his wife in Newport Beach. http://caseydorman.com

FRIDAY READS is a weekly feature showcasing writers based in Orange County, Calif. If you’re interested in submitting an excerpt, check out our SUBMISSIONS page.

Excellent read! I feel for George being married to that harpy. Piqued my interest in the mystery.